Doctor Pretorius: Do you know who Henry Frankenstein is, and who you are?

The Monster: Yes, I know. Made me from dead. I love dead… hate living.

Doctor Pretorius: You are wise in your generation…

BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1935)

I was initially reluctant to write this. In the wake of the much-loved director’s recent death, I’m pretty confident the web currently has quite enough George A. Romero retrospectives to be getting along with. But once the dust had settled I figured the web could handle one more – and this was for me more than anybody else – about exploring something that had a profound impact on my inner life. Though obviously if anyone else is interested in my thoughts on the matter then I’m delighted and flattered to share them here. The following is a personal rumination, not a scholarly treatise but an opinionated take on Romero’s work and its place in horror history and modern mythology.

As I’ve already suggested, there is no shortage of other commentators memorialising Romero – some surely substantially better qualified to do so than myself, others perhaps rather less so… Among the former are numerous people lucky enough to have known the director personally. They provide ample testimony to what an intelligent, big-hearted and generous human being George was, particularly when approached by starstruck fans. (I suspect however this may have ultimately have proven a mixed blessing – something I touched on in a previous blog, which you can read here…) The latter, less illuminating eulogists, if nothing else, serving to underline Romero’s understated, yet monolithic cultural significance. His influence stretches well beyond the horror genre, leading to numerous mainstream journalists being obliged to pen rushed appreciations, pieces that rather too evidently took them far outside their comfort zones.

Few imaginary creations enjoy the same cult status on the cutting-edge of mainstream culture as Romero’s zombie world. Perhaps only H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos can compete for sheer contagious ubiquity across numerous formats and media. Though while Lovecraft’s mad gods and alien demons may have crossed as many media boundaries as Romero’s cannibal cadavers, they’ve never enjoyed the same high profile recognition factor. Within the realms of the horror genre, most of the monsters that haunt our collective subconscious – vampires, werewolves, and such – were drawn from arcane European folklore and Gothic literature, refracted through a Hollywood lens in the early Twentieth Century.

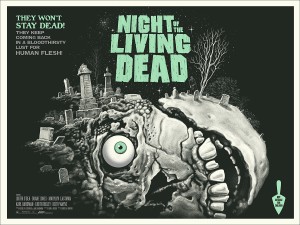

The past fifty years have arguably only seen two significant additions to our universally-recognised pantheon of pop culture monsters – both all-American and conspicuously modern. The first is the quasi-supernatural serial killer, introduced in films like HALLOWEEN (1978) and FRIDAY THE 13TH (1980). The second, of course, is the flesh-eating ghoul Romero introduced in NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968), and developed in DAWN OF THE DEAD (1978) and DAY OF THE DEAD (1985). How many individuals can lay claim to have effectively given birth to a bona fide contemporary myth? For, make no mistake, modern congregations of cinema-goers look upon their idols in the modern cathedral of the multiplex in just the same way that our distant ancestors revered the likes of Wotan or Zeus in the temples of the pre-Christian world.

The past fifty years have arguably only seen two significant additions to our universally-recognised pantheon of pop culture monsters – both all-American and conspicuously modern. The first is the quasi-supernatural serial killer, introduced in films like HALLOWEEN (1978) and FRIDAY THE 13TH (1980). The second, of course, is the flesh-eating ghoul Romero introduced in NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968), and developed in DAWN OF THE DEAD (1978) and DAY OF THE DEAD (1985). How many individuals can lay claim to have effectively given birth to a bona fide contemporary myth? For, make no mistake, modern congregations of cinema-goers look upon their idols in the modern cathedral of the multiplex in just the same way that our distant ancestors revered the likes of Wotan or Zeus in the temples of the pre-Christian world.

George’s mythology of a world overrun by shambling ghouls has thrown a shadow that stretches way beyond his numerous cinematic imitators, and the record-breaking WALKING DEAD TV show, and indeed beyond the horror genre itself. Everyone under a certain age knows that zombies are rotting dead people that eat brains. In a surreal recent evolution, many affiliated products are now comical or even cuddly in tone, with an increasing number marketed to a younger demographic, typified perhaps by the hit PLANTS VERSUS ZOMBIES computer game and its numerous spin-offs – it’s also possible to buy zombie slippers, zombie candy, ad infinitum – as Romero’s zombies evolved from cult figures to corporate mascot.

George’s mythology of a world overrun by shambling ghouls has thrown a shadow that stretches way beyond his numerous cinematic imitators, and the record-breaking WALKING DEAD TV show, and indeed beyond the horror genre itself. Everyone under a certain age knows that zombies are rotting dead people that eat brains. In a surreal recent evolution, many affiliated products are now comical or even cuddly in tone, with an increasing number marketed to a younger demographic, typified perhaps by the hit PLANTS VERSUS ZOMBIES computer game and its numerous spin-offs – it’s also possible to buy zombie slippers, zombie candy, ad infinitum – as Romero’s zombies evolved from cult figures to corporate mascot.

While imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, if there was one topic inclined to make the otherwise affable George spit blood in interview, it’s the way so many of his imitators have made so much exploiting something he created. He has a point. His legendary debut NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD has been cited as the most profitable indie picture ever made, but after some dodgy dealing in distribution, Romero barely saw a cent. It set something of a pattern for George, whose career was cursed to be one where his colossal creative contribution to culture was never quite reflected in career or commercial terms. Some have even suggested that NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD’s most important innovation wasn’t creative, but in demonstrating how much money a very modestly-budgeted horror picture could make.

Romero can surely be forgiven for some sour grapes at the number of people who profited in his creative wake, particularly those unwilling to even acknowledge their inspiration. One of the more interesting examples is RESIDENT EVIL. It began as a 1996 hit big budget horror computer game, featuring Romero-style zombies, which now boasts six sequels. The game’s success led to a 2002 film adaptation, followed by a franchise which currently has five sequels of its own under its belt. For once, it looked like George might actually enjoy a little of the lucrative action, as he was commissioned to helm a trailer for the second RESIDENT EVIL game, then approached to write and direct the movie version. He would later describe the experience as ‘the biggest damn shame’ of his career.

‘We busted balls writing drafts of that screenplay’, the director later reflected. ‘I’m talkin’ marathons, seventy-two hours straight. I really wanted this project… I was hooked. Deep in my heart, I felt that ResEv was a rip-off of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. I had no legal case, but I was resentful. And torn… because I liked the video game. I wanted to do the film partly because I wanted to say, “Look here! This is how you do this shit!”’ The official version was that Romero was dropped because they didn’t like how he did that shit – specifically his script. Studio bosses favoured a version that focused on action rather than horror. Hollywood gossip had it that senior studio noses were out of joint over George being too frank in interviews about how much he thought RESIDENT EVIL owed to his own work.

This is, of course, all history now. Romero’s script, now it’s become available, certainly reads far better than the Paul W. S. Anderson version the studio ultimately went with. Yet that doesn’t mean that studio heads were necessarily wrong. Even if the critics dismissed the Anderson film as a vapid turkey, it was a very popular turkey, and the resultant franchise continues to be a huge money-spinner. NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD might’ve made a lot of money relative to its poverty row budget, but these were sums that would barely register on the balance sheets of Capcom and Sony, the corporations behind RESIDENT EVIL in its various incarnations. And they clearly concluded that Anderson’s action approach had a broader commercial appeal than Romero’s horror, whatever the critics might say.

This is, of course, all history now. Romero’s script, now it’s become available, certainly reads far better than the Paul W. S. Anderson version the studio ultimately went with. Yet that doesn’t mean that studio heads were necessarily wrong. Even if the critics dismissed the Anderson film as a vapid turkey, it was a very popular turkey, and the resultant franchise continues to be a huge money-spinner. NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD might’ve made a lot of money relative to its poverty row budget, but these were sums that would barely register on the balance sheets of Capcom and Sony, the corporations behind RESIDENT EVIL in its various incarnations. And they clearly concluded that Anderson’s action approach had a broader commercial appeal than Romero’s horror, whatever the critics might say.

Whether by accident, temperament or design – George’s lack of reverence for studio bigwigs was the stuff of legend – Romero was destined to spend most of his career outside of the Hollywood system, as a big fish in the cult cinema pond. A few of the obituaries bewailed this, wondering why he never troubled the Oscar selection committees, but I think they’re missing the point. Good horror is unsettling, troubling, and tests taboos – hence not inclined to please committees. It is a place for mavericks and misfits. Horror is all but alone as a genre in having so many of its landmark films being the product of independent filmmakers on low budgets. To return to the thread we abandoned a few paragraphs back, Romero’s Dead Trilogy isn’t unique, even within the horror genre, as a film made on a shoestring that went on to become a critical and cultural phenomenon, though it is a definitive example.

Perhaps it was the explicit, bloody brutality featured in Romero’s debut that made it so influential, or maybe its raw, almost documentary feel, or even employing an African American actor as its hero way back in the Sixties? Perhaps… Though there are other contenders for the majority of these innovations. Most notably director Herschell Gordon Lewis, who’d already been selling low-rent gore to cinema-goers for five years when NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD debuted. Surely the film’s most obvious invention is the likeliest contender, namely the zombies themselves. Certainly there had been zombie films before, but these had been the undead of Haitian voodoo tradition – effectively post mortem slave labour – not the cannibalistic cadavers Romero introduced in NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. Indeed, the word ‘zombie’ is conspicuous by its absence in the film (and largely used sparsely in Romero’s other ‘Dead’ films), with the more accurate term ‘ghoul’ being preferred. More accurate as ghouls, unlike zombies, did traditionally feast on human flesh.

(As an aside, the first time I remember reading anyone taking Romero remotely seriously was in David Pirie’s pioneering 1977 study THE VAMPIRE CINEMA. Interestingly, Pirie doesn’t foretell a new zombie (or ghoul) subgenre, instead predicting that NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD offered a new direction for future vampire films. I have some time for this off-target prediction, as in many respects Romero’s walking dead resemble the original vampires of medieval European folklore more closely than the cloaked cliché we are familiar with courtesy of Hollywood. Revenants, as historians often refer to our prototypical vampires, were not dapper aristocrats, but like Romero’s undead were malodorous and mindless walking corpses that menaced their former friends, family and neighbours.)

(As an aside, the first time I remember reading anyone taking Romero remotely seriously was in David Pirie’s pioneering 1977 study THE VAMPIRE CINEMA. Interestingly, Pirie doesn’t foretell a new zombie (or ghoul) subgenre, instead predicting that NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD offered a new direction for future vampire films. I have some time for this off-target prediction, as in many respects Romero’s walking dead resemble the original vampires of medieval European folklore more closely than the cloaked cliché we are familiar with courtesy of Hollywood. Revenants, as historians often refer to our prototypical vampires, were not dapper aristocrats, but like Romero’s undead were malodorous and mindless walking corpses that menaced their former friends, family and neighbours.)

However you like to imagine them, though, the proliferation of vampires dating back to the dawn of horror cinema prove that our fear of the re-animated dead wasn’t what made George’s ghouls special. Similarly, the cannibalism taboo, while clearly key to the Romero recipe, was hardly anything new in 1968, featuring in numerous previous horror films. It’s central to the plot of the Sweeney Todd story, which was first filmed in 1926, for example, and figures in most werewolf films. Romero’s’ flesh-eating scenes were notably graphic, but no more so than Herschell Gordon Lewis’s debut gore film BLOOD FEAST, also a cannibal movie of sorts. Yet while BLOOD FEAST was camp and cartoonish in its gleeful ineptitude, NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD exploited its minimal production values to attain a grim newsreel quality that contributed to its impact on unsuspecting audiences.

However you like to imagine them, though, the proliferation of vampires dating back to the dawn of horror cinema prove that our fear of the re-animated dead wasn’t what made George’s ghouls special. Similarly, the cannibalism taboo, while clearly key to the Romero recipe, was hardly anything new in 1968, featuring in numerous previous horror films. It’s central to the plot of the Sweeney Todd story, which was first filmed in 1926, for example, and figures in most werewolf films. Romero’s’ flesh-eating scenes were notably graphic, but no more so than Herschell Gordon Lewis’s debut gore film BLOOD FEAST, also a cannibal movie of sorts. Yet while BLOOD FEAST was camp and cartoonish in its gleeful ineptitude, NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD exploited its minimal production values to attain a grim newsreel quality that contributed to its impact on unsuspecting audiences.

This unsettling sense of reality – of a film that felt uncomfortably reminiscent of local news reports – has been cited as the factor that distinguished Romero’s debut feature. Maybe, though it isn’t true of the two succeeding sequels, without which his Dead World would never have become so iconic. In truth, an idea needs to work on several levels in order to burrow as deeply into our collective subconscious as this. Some of these will have a more profound resonance with some than others, and it is the ability to touch a lot of people in a lot of subtly different ways – on different levels and wavelengths – that transforms something from a cult favourite to a cultural phenomenon.

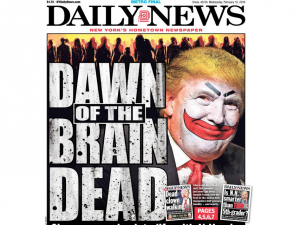

My own take on what makes the Romero Dead universe so powerful was most perfectly expressed in DAY OF THE DEAD, the most chillingly bleak of the Trilogy. It is the dread of being torn apart by idiots. If zombies ever gave me nightmares – and they did – it was this dread of being literally ripped asunder by countless grasping hands and teeth. If I analyse it, I think for me, zombies function as a political horror of sorts – a manifestation of the sense that we are surrounded by drones who look and behave much like us, but are slower, more instinct-driven, and destined to overwhelm us by sheer weight of numbers. It is the taboo fear that democracy is inherently-flawed, because most people are too stupid and self-interested to be trusted. In my subconscious, Romero’s dead were the mindless majority who refused to stay silent, the softly moaning mob driving us towards the precipice with their stubborn idiocy.

My own take on what makes the Romero Dead universe so powerful was most perfectly expressed in DAY OF THE DEAD, the most chillingly bleak of the Trilogy. It is the dread of being torn apart by idiots. If zombies ever gave me nightmares – and they did – it was this dread of being literally ripped asunder by countless grasping hands and teeth. If I analyse it, I think for me, zombies function as a political horror of sorts – a manifestation of the sense that we are surrounded by drones who look and behave much like us, but are slower, more instinct-driven, and destined to overwhelm us by sheer weight of numbers. It is the taboo fear that democracy is inherently-flawed, because most people are too stupid and self-interested to be trusted. In my subconscious, Romero’s dead were the mindless majority who refused to stay silent, the softly moaning mob driving us towards the precipice with their stubborn idiocy.

It’s a pessimism also manifest in the living characters of Romero’s dystopia – almost every disaster and fatality results from the selfishness and stupidity of the survivors themselves. Romero’s world gives plenty for pessimists to get their teeth into. If God isn’t dead, then He has abandoned humanity in disgust. You cannot trust the military, the media, medicine or politicians and scientists. Even family and lovers can no longer be relied upon. In this grim future, only a sense of honour, dogged determination, and the virtues of friendship offer any kind of support. It is, I believe, very much a Generation X dystopia, fed by those who saw the optimism of the Sixties swept away in a wave of building violence, replaced only by cynicism and world-weary misanthropy. In Romero’s world, humans are often little better than zombies, but we’re all we’ve got.

Of course there are numerous other interpretations of the subtexts that helped make George’s zombies so iconic. DAWN OF THE DEAD, for example, is easy to interpret as a gory parody of the rampant 80s consumerism on the horizon when the film debuted (many horror fans still hear the film’s classic Goblin soundtrack whenever they find themselves in a shopping mall). A lot of critics see the influence of the building violence of the civil rights clashes that began to dominate news bulletins in the Sixties as key to the tone and themes informing NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. However, when VANITY FAIR’s Eric Spitznagel asked Romero about the symbolism of the living dead in 2010, the director was sceptical. ‘To paraphrase Freud’, began the journalist, ‘sometimes things have symbolism and sometimes a cigar is just a cigar. Are the zombies in your movies always a metaphor, or are they sometimes just bloodthirsty walking corpses?’

‘To me, the zombies have always just been zombies,’ responded Romero. ‘They’ve always been a cigar. When I first made NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, it got analyzed and overanalyzed way out of proportion. The zombies were written about as if they represented Nixon’s Silent Majority or whatever. But I never thought about it that way. My stories are about humans and how they react, or fail to react, or react stupidly. I’m pointing the finger at us, not at the zombies. I try to respect and sympathize with the zombies as much as possible.’ George’s perspective appears to rather contradict my own interpretation of what makes his Dead films so effective. But, as I’ve emphasised before, this is a personal view, and, more importantly, perhaps the essence of the potency of his mythology is in its adaptability and origins in the subconscious. Romero was just going for what felt effective. Good horror comes from the subconscious – addresses contemporary fears obliquely – lending it that universal quality open to multiple interpretations.

On another minor tangent, I wonder if truly iconic horror also needs to mix a little guilty yearning in with the overt dread. The sexual overtones of the modern vampire are widely accepted, werewolves allow us to fantasise ourselves supernaturally powerful and unfettered by the dictates of law and morality, and so forth. But what faint silver lining can the zombie myth offer? One obvious fantasy explored in DAWN OF THE DEAD is the retail nirvana of a free shopping spree in a state-of-the-art mall. While many focus on the film’s undertone that suggests that the zombies are a metaphor for blind consumers, the sequences where the film’s protagonists enjoy the mall’s bounty gratis are the most tranquil – even happy – in a movie otherwise dominated by unrelenting stress and trauma. A world where law has broken down does have its advantages.

On another minor tangent, I wonder if truly iconic horror also needs to mix a little guilty yearning in with the overt dread. The sexual overtones of the modern vampire are widely accepted, werewolves allow us to fantasise ourselves supernaturally powerful and unfettered by the dictates of law and morality, and so forth. But what faint silver lining can the zombie myth offer? One obvious fantasy explored in DAWN OF THE DEAD is the retail nirvana of a free shopping spree in a state-of-the-art mall. While many focus on the film’s undertone that suggests that the zombies are a metaphor for blind consumers, the sequences where the film’s protagonists enjoy the mall’s bounty gratis are the most tranquil – even happy – in a movie otherwise dominated by unrelenting stress and trauma. A world where law has broken down does have its advantages.

Which leads us onto an even more morally troubling wish-fulfilment fantasy which Romero’s dystopian future promises. Romero definitely encourages his audience to condemn rather than identify with the gun-happy red-neck vigilantes and nomadic biker gangs in his films that actually seem to be enjoying the lawless zombie apocalypse. But there’s no denying that much of the zombie media that’s followed in the wake of Romero’s Dead Trilogy panders to the adrenaline rush of hunting humans, a taboo pastime legitimised (and made easier) by the post mortem nature of the quarry. It’s a tempting but disturbing fantasy – that once dehumanised by death, we can simply kill the mindless hordes who frustrate and threaten us, without moral qualms or fear of legal repercussions. In light of the increasing number of mass shootings plaguing the USA, it isn’t difficult to see how this notion quickly takes us into very dark, contraversial territory. How you deal with that essentially pivots on whether you see horror cinema as a harmless pressure valve for forbidden fantasies, or a problematic trigger for taboo behaviour. (I, of course, am very much of the former opinion.)

It’s probably worth addressing the undead elephant in the room right now. While I’ve been repeatedly referring to Romero’s Dead Trilogy, he’s actually made six zombie films – and most of the comments from the director I’ve referenced or quoted come from the period while he was making these three subsequent films. There’s a tendency to overlook these later movies among many horror veterans – mostly due to a conviction that they aren’t nearly as good as the first three. After a twenty year hiatus from directing the dead, Romero’s LAND OF THE DEAD debuted in 2005 to great anticipation (perhaps too much). It was a commercial and critical success, but alienated many diehard fans of the original Trilogy. Very much a studio picture, it felt too slick and commercial, too forced – as if Romero was self-consciously trying to cram the social satire into the script, which had once been a wholly organic component of his film-making. Most damningly, it wasn’t as good as the DAWN OF THE DEAD remake that had come out the year before.

It’s probably worth addressing the undead elephant in the room right now. While I’ve been repeatedly referring to Romero’s Dead Trilogy, he’s actually made six zombie films – and most of the comments from the director I’ve referenced or quoted come from the period while he was making these three subsequent films. There’s a tendency to overlook these later movies among many horror veterans – mostly due to a conviction that they aren’t nearly as good as the first three. After a twenty year hiatus from directing the dead, Romero’s LAND OF THE DEAD debuted in 2005 to great anticipation (perhaps too much). It was a commercial and critical success, but alienated many diehard fans of the original Trilogy. Very much a studio picture, it felt too slick and commercial, too forced – as if Romero was self-consciously trying to cram the social satire into the script, which had once been a wholly organic component of his film-making. Most damningly, it wasn’t as good as the DAWN OF THE DEAD remake that had come out the year before.

If it had one undoubted virtue, then it was at least better than his 2007 follow-up DIARY OF THE DEAD. DIARY… felt as if George was reacting to fan criticism of LAND… by returning to his roots with a low budget picture that referenced cutting-edge culture. The result – stuffed with awkward nods to social media and found footage style filming – was embarrassingly close to watching your ageing uncle trying to get hip with the kids. In 2009 he released SURVIVAL OF THE DEAD, a film which in turn had little in its favour beyond making DIARY OF THE DEAD seem good by comparison. Just prior to his death, Romero announced that he was preparing a script entitled ROAD OF THE DEAD (the announcement prompted me to wonder if CAR CRASH OF THE DEAD might be more apt) inspired by one of the worst ideas from his worst film (zombies driving cars in SURVIVAL OF THE DEAD). It seemed depressingly plausible that Romero had seen how George Miller had revamped his 80s MAD MAX trilogy with FURY ROAD in 2015, and wondered if he could follow suit.

If it had one undoubted virtue, then it was at least better than his 2007 follow-up DIARY OF THE DEAD. DIARY… felt as if George was reacting to fan criticism of LAND… by returning to his roots with a low budget picture that referenced cutting-edge culture. The result – stuffed with awkward nods to social media and found footage style filming – was embarrassingly close to watching your ageing uncle trying to get hip with the kids. In 2009 he released SURVIVAL OF THE DEAD, a film which in turn had little in its favour beyond making DIARY OF THE DEAD seem good by comparison. Just prior to his death, Romero announced that he was preparing a script entitled ROAD OF THE DEAD (the announcement prompted me to wonder if CAR CRASH OF THE DEAD might be more apt) inspired by one of the worst ideas from his worst film (zombies driving cars in SURVIVAL OF THE DEAD). It seemed depressingly plausible that Romero had seen how George Miller had revamped his 80s MAD MAX trilogy with FURY ROAD in 2015, and wondered if he could follow suit.

It’s painful to see somebody you admire so much struggle to rediscover their creative mojo, but there’s no denying that the final decade of George Romero’s career saw him make a succession of films that made many dedicated admirers wince. He’s certainly created the Dead World which the likes of THE WALKING DEAD and Brad Pitt’s 2013 big-budget blockbuster WORLD WAR Z exploited so lucratively and, in some views, mined to extinction. ‘Because of WORLD WAR Z and THE WALKING DEAD, I can’t pitch a modest little zombie film, which is meant to be sociopolitical,’ he told Indiewire in 2016. ‘I used to be able to pitch them on the basis of the zombie action, and I could hide the message inside that. Now, you can’t. The moment you mention the word “zombie,” it’s got to be, “Hey, Brad Pitt paid $400 million to do that.”’

Yet George’s conviction that there was still life in the zombie movie may have been a triumph of nostalgia over experience. While zombie films can still be made cheaply enough to practically guarantee a profit regardless of quality, most serious horror fans greet the advent of a new zombie movie with a mixture of suspicion and dismay. There are good zombie films being released, but increasingly it has become the subject of preference for lazy film-makers with little imagination, a tiny budget, and an even more scant respect for their audience. It is to Romero’s credit that, before horror started to enjoy some degree of critical respect (due in no small part to his own efforts), he didn’t disown the genre, but remained faithful to the zombies that had made his career, though his loyalty may have blinded him to the rot setting in to the subgenre he’d created.

It’s probably worth noting at this stage that, though he will always be remembered as ‘the Father of the Zombie film’, that George also directed ten other films, all of which are worth seeing, and most of which share that distinctive Generation X pessimism that characterises his Dead World. THE CRAZIES (1973) takes his dystopian view of a world menaced by apocalyptic plague and arguably makes it even darker by removing the undead. MARTIN (1978) is a pitch-perfect blend of Gothic horror and post-modern arthouse cinema that revives vampirism for a cynical age. KNIGHTRIDERS (1981) reinvents Arthurian mythology in Romero’s own unique style. CREEPSHOW (1982) proved George could do lurid old-school scares aimed at the monster kid generation…

Perhaps George Romero should have tried to revisit one of these projects in order to rediscover his mojo? Or, better still, have chanced his arm on something wholly original? Of course, it’s possible that if he was struggling to raise the finance for a Dead picture with his name attached, finding the funds for anything else would’ve been impossible. Regardless, even if you share my scepticism over his recent output, Romero has left cinema – and hence modern mythology – with a unique and powerful legacy. And even if zombie movies are increasingly passé, the idea behind them seems more relevant to me every year. If, as I suggest, that zombies are the democratic nightmare – of humanity dragged down by a morass of lumpen selfishness and raw stupidity – then could there be a better metaphor for a world menaced by Trump and Brexit?…

Perhaps George Romero should have tried to revisit one of these projects in order to rediscover his mojo? Or, better still, have chanced his arm on something wholly original? Of course, it’s possible that if he was struggling to raise the finance for a Dead picture with his name attached, finding the funds for anything else would’ve been impossible. Regardless, even if you share my scepticism over his recent output, Romero has left cinema – and hence modern mythology – with a unique and powerful legacy. And even if zombie movies are increasingly passé, the idea behind them seems more relevant to me every year. If, as I suggest, that zombies are the democratic nightmare – of humanity dragged down by a morass of lumpen selfishness and raw stupidity – then could there be a better metaphor for a world menaced by Trump and Brexit?…