The following is something of blast from the past, revisiting something I wrote for a horror site exactly four years ago reviewing an ancient BBC TV series entitled SUPERNATURAL, just then released on DVD for the first time. The site’s rebranded since, and all of my contributions cast into oblivion in the process. But this piece came to mind today, so I excavated the depths of my old hard drives and found a copy. I can’t vouch for its quality – I’m a very poor judge of my own work – but it did seem pertinent again for some odd reasons.

One reason is that Christmas is almost upon us, and I’m keen to support the Yuletide ghost story tradition. Perhaps my favourite manifestation of this are the BBC’s GHOST STORIES FOR CHRISTMAS. At one point broadcast every year in the seventies, they have become increasingly intermittent. For those who’ve practically worn out their BBC GHOST STORY FOR CHRISTMAS discs, SUPERNATURAL offers a possible alternative, as another Gothic season from the BBC in the same era. But is it a worthy alternative?

One reason is that Christmas is almost upon us, and I’m keen to support the Yuletide ghost story tradition. Perhaps my favourite manifestation of this are the BBC’s GHOST STORIES FOR CHRISTMAS. At one point broadcast every year in the seventies, they have become increasingly intermittent. For those who’ve practically worn out their BBC GHOST STORY FOR CHRISTMAS discs, SUPERNATURAL offers a possible alternative, as another Gothic season from the BBC in the same era. But is it a worthy alternative?

Another, less obvious, reason for resurrecting my SUPERNATURAL piece is STAR WARS. The new STAR WARS movie, THE LAST JEDI, is currently causing the now obligatory cycle of hype, hysteria, backlash, and backlash to the backlash. I can’t comment on the virtues of the film itself, having not seen it, but was curious enough to watch its predecessor THE FORCE AWAKENS when it surfaced on Netflix a couple of nights back. I think I’d characterise my reaction as underwhelmed. It wasn’t terrible, just seriously cheesy and predictable.

Another, less obvious, reason for resurrecting my SUPERNATURAL piece is STAR WARS. The new STAR WARS movie, THE LAST JEDI, is currently causing the now obligatory cycle of hype, hysteria, backlash, and backlash to the backlash. I can’t comment on the virtues of the film itself, having not seen it, but was curious enough to watch its predecessor THE FORCE AWAKENS when it surfaced on Netflix a couple of nights back. I think I’d characterise my reaction as underwhelmed. It wasn’t terrible, just seriously cheesy and predictable.

In fairness though, I’m not the target audience – it’s a family-friendly franchise and I’m only a lukewarn sci-fi fan – and am more interested in the fan phenomenon surrounding it. Because nothing about THE FORCE AWAKENS, or indeed any of the other films, seems to me to justify the frenzy of excitement – even obsession – they engender these days. And I don’t just mean among strangers, but friends and acquiantances whose opinions I generally value. But the STAR WARS hysteria genuinely baffles me.

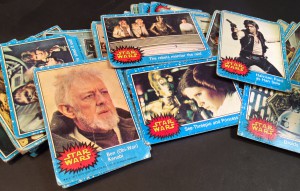

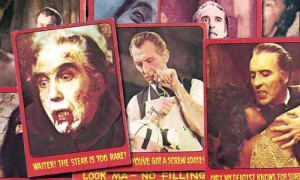

Having said which, I have very much enjoyed a STAR WARS film. That one being STAR WARS itself. I thought it was great. But I was ten. So this hysteria can’t just be a generational thing. Many of the STAR WARS obsessives weren’t even born when the franchise debuted in 1977. And I don’t remember being that struck by it. A good illustration of this is that I collected the set of STAR WARS bubblegum cards, then sold them to a friend to finance collecting a Hammer horror set instead. I clearly had my priorities right back then.

Having said which, I have very much enjoyed a STAR WARS film. That one being STAR WARS itself. I thought it was great. But I was ten. So this hysteria can’t just be a generational thing. Many of the STAR WARS obsessives weren’t even born when the franchise debuted in 1977. And I don’t remember being that struck by it. A good illustration of this is that I collected the set of STAR WARS bubblegum cards, then sold them to a friend to finance collecting a Hammer horror set instead. I clearly had my priorities right back then.

And while STAR WARS faded from my imagination fairly fast, something else I watched that year which left an abiding mark on my young imagination. That was the BBC’s SUPERNATURAL. It probably helped that after being screened once, the series seemed to vanish. Only a tatty copy of the novelisation remained to confirm me to me that I hadn’t simply dreamed it. By comparison, of course, while STAR WARS may have faded from the spotlight for most of the eighties and nineties, it’s become absurdly ubiquitous in the twenty-first century.

And while STAR WARS faded from my imagination fairly fast, something else I watched that year which left an abiding mark on my young imagination. That was the BBC’s SUPERNATURAL. It probably helped that after being screened once, the series seemed to vanish. Only a tatty copy of the novelisation remained to confirm me to me that I hadn’t simply dreamed it. By comparison, of course, while STAR WARS may have faded from the spotlight for most of the eighties and nineties, it’s become absurdly ubiquitous in the twenty-first century.

But there are parallels between the two beyond the coincidence of first airing on the same year. Specifically, relating to fan reaction. I had been sat in front of THE FORCE AWAKENS a couple of nights ago, one eyebrow raised smugly at its sundry shortcomings. The acting was largely adequate at best, the plot a confection of the absurdly improbable and cheesily predictable, glued together with clumsy winks to the gallery over laboured in-jokes. I just didn’t get it.

But that feeling was not unlike the one I experienced when watching THE SUPERNATURAL for the first time in nearly 40 years. But in this case I was a fan. Looking at it through the reviewer’s eye it was difficult to justify my deep affection for the series. If the script of THE FORCE AWAKENS had a surfeit of cheese, then the acting in THE SUPERNATURAL was a feast of ham. In terms of absurd improbability and predictability SUPERNATURAL certainly gives any of the STAR WARS films a good run for their money. I guess it all comes down to personal proclivities.

Which is hardly an earth-shattering notion, but one which I guess it’s easy for us all to forget. Which is part of what I explored in this fragment from the archives. That and how everyone should like SUPERNATURAL because it’s obviously way better than dreary old STAR WARS. So there!…

THE BBC’S SUPERNATURAL AND THE SIREN SONG OF

NOSTALGIA

Watching the recent BFI release of the vintage BBC series SUPERNATURAL, and seeing

the widely varied reception it experienced from other reviewers, inspired a few

thoughts on broader topics. Hence I beg the indulgence of the Brutal as Hell faithful

as I open my review of this long-lost Gothic TV show with a few thoughts on the way

we all watch the genre screen entertainment we enjoy, and how even the most

scrupulous of reviewers can find their judgement swayed by ineffable bias. In the

noble quest for objectivity, it can be easy to forget how subjective an experience

watching a film or television episode can be.

We all know, of course, that assessing a film’s value is almost definitively a matter of

opinion. But I’m thinking here of other subtler, more ephemeral factors that can have

a heavy impact on our appreciation of something like a film, without us really

noticing. The mood you’re in, for example. A crabby mood can turn a good movie

into a piece of crap: a sunny demeanour transform a mediocre production into a

personal favourite. I’ve known genre devotees dismiss classics, then fall in love upon

rewatching them, before casting their memory back and recalling unrelated clouds on

their horizon which blighted the experience of viewing the innocent production first

time round.

All sorts of other external factors that have nothing to do with the film per se –

company, health, personal prejudice, etc., etc. – but can play a pivotal role in what

impression the production leaves upon you. The one I’m focusing on here is age.

Somebody once said something along the lines of ‘You never see your favourite film

over the age of 25’. While I fear the exact origin and wording of this quote eludes me,

I think there’s much virtue in the sentiment. That for a movie to really get under your

skin to the point where you adore it with that almost irrational fervour, it pays for it to

hit you young, when you still possess at least a little of that wide-eyed sense of

wonder that life conspires to slowly beat out of us.

It’s possible to see manifestations of this phenomenon in all manner of media. Only

the rosy-tinted spectacles of cherished childhood memory can explain the hold shows,

films and franchises originally aimed primarily at kids – such as Dr Who, Lego, or

Marvel superheroes – still exert over so many well into middle age. Indeed, if

anything, that grip gets stronger, as fans devote skills and resources accrued in

adulthood to analyse, criticise and obsess over works of fiction only ever designed to

withstand the less rigorous scrutiny of children. Part of the visceral hatred many fans

feel for the incessant stream of Hollywood remakes comes from a wholly reasonable

dismay at the turgid lack of imagination and vision they represent. But it also comes

from a more irrational, ineffable fear that remaking the treasured cultural artefacts of

our youth might somehow dilute or even destroy them.

To return to horror, there’s a monthly genre film night hosted in a nightclub near

To return to horror, there’s a monthly genre film night hosted in a nightclub near

where I live. It’s great fun, but I’ve noticed that everything screened has come from

the 1980s. When I drew the organisers’ attention to this and suggested they dig further

into the vaults, or considered more recent favourites, they were unenthusiastic,

explaining that they had to show ‘the classics’ in order to draw a crowd. It dawned on

me that it was a generational thing. They weren’t seriously suggesting that every

classic horror film was made between 1980 and 1990. But as thirty-somethings, never

thought to question the assumption that 80s horror films, as the ones that they grew up

with, were also the ones that automatically commanded the most affection among

fans, the movies which seem most magical, for which they’re most willing to forgive

failings and celebrate clichés.

The reason for this very lengthy, tangential preamble is that, as a somewhat more

vintage genre devotee, I feel much the same about 1970s horror. So, the past few

hundred words are in part my mea culpa, a confession that in reviewing THE SUPERNATURAL I am incapable of giving an opinion devoid of chronological baggage. This bias is further weighted by the obscurity of the series. I saw it as a child when it first

screened way back on BBC1, on eight successive Saturday nights in the summer of

1977.  SUPERNATURAL then, in true Gothic style, effectively disappeared without

SUPERNATURAL then, in true Gothic style, effectively disappeared without

trace. Soon, only the fact that I’d been sufficiently impressed to buy the paperback

novelisation remained as proof that it had been anything more than a childhood

nightmare. That, and a series of potent images that remained seared into my

impressionable imagination thereafter…

SUPERNATURAL was never screened again, didn’t appear on tape with the advent of the

video boom of the 1980s, and with the arrival of the internet revolution in the

following decade, remained elusive, early searches yielding little to confirm its

existence. In TEN YEARS OF TERROR, Harvey Fenton and David Flint’s exemplary and

exhaustive 2001 study of 70s Brit screen horror, SUPERNATURAL enjoys only the briefest

of coverage, illustrated by a scan from the cover of the same paperback tie-in I

possessed. Inevitably, perhaps, the show’s elusiveness leant it an almost mythic aura

among dedicated devotees of vintage horror. Some years back I finally tracked down a

copy of the show via grey dealers on eBay, some three decades after it first frightened

me, but the quality of the recordings were too poor to really give an accurate

assessment of the series.

Hence, it was with great excitement that I recently received the two SUPERNATURAL

Hence, it was with great excitement that I recently received the two SUPERNATURAL

DVDs. So, the big question – was it worth the wait? (Or, indeed, for you patient

reader, worth wading through such a protracted prelude?) The series consists of seven

tales on classic Gothic themes – ghosts, werewolves, doppelgangers, split

personalities, sentient mannequins, Frankenstein, vampires – in eight 50 minute

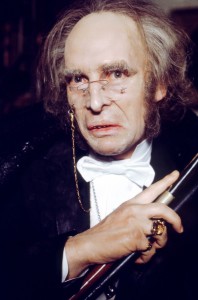

episodes (one story is in two parts). The cast boasts a cast of distinguished Brit

character actors – Robert Hardy, Billie Whitelaw, Jeremy Brett, Denholm Elliot – who

match the rich material with highly theatrical, even melodramatic performances which

often makes many of the tales feel more like stage plays than TV shows.

The unifying thread that bookends each episode centres on the Club of the Damned,

an exclusive Victorian London gentleman’s institution. Perhaps the most exclusive, as

aspirant candidates must tell a tale of dread to established members – if it should fail

to terrify the assembled company, then they must pay the ultimate penalty, and are

never seen again. It’s an intriguing idea, and little details – such as a Satanic

baphomet symbol on a table – suggest an urbane infernal fellowship along the lines of

a latterday Hellfire Club. But it’s never really explored, the threat of extinction for

failed candidates not delved into, as what we see of the members hardly smacks of the

tension of the omnipresence of death. Indeed the Club members never really seem

frightened at the end of any of the stories, from which the viewer can only conclude

that all of the hopeful candidates got the chop once the final credits had rolled.

Of course, the Club of the Damned represents only the entrance and exit to the main

Of course, the Club of the Damned represents only the entrance and exit to the main

event, but the failure to exploit this tantalising angle is somewhat characteristic of

SUPERNATURAL overall, of promising ideas wasted and evocative paths uncovered but

not travelled. This is also, perhaps, the show’s strength. For – from its opening of

eerie organ music and gargoyles, to the peels of maniacal laughter that frequently

presage the final credits – SUPERNATURAL is full-on, industrial-strength Gothic. And

much pure Gothic is about unexplored roads and decayed ideologies, seldom fully

explained or resolved. Connoisseurs of the aesthetic will find a feast to relish in

SUPERNATURAL, from the lushly stifling Victoriana of the sets and costumes, to the florid

dialogue and overwrought acting.

Casual viewers will likely yawn at the verbose scripts and occasionally snigger at

some of the fruitier lines and camper delivery. Jeremy Brett’s descent into madness in

the episode ‘Mr Nightingale’ – complete with gurning at breakfast, black seagull

impersonations, and animated omelette debates – is hard to take seriously. Some DIY

standard visual effects don’t help either, suggesting a budget and level of

sophistication comparable with the less-than-special-effects of DR WHO of the day.

Though, just as some sci-fi devotees can see past the effects to enjoy the substance of

Pertwee/Baker era DR WHO, so aficionados of small screen Gothic should forgive

many of the more dated elements in SUPERNATURAL. In SUPERNATURAL’s stronger episodes, such as in the final part ‘Dorabella’ – a clever amalgam of CARMILLA and DRACULA – the subtler effects can be highly effective.

It was images from ‘Dorabella’ in particular – of a fly-flecked corpse, a monstrous

wedding ring, an eyeless curse – that stuck with me long after I’d watched the series

as a child, its atmosphere of dread and decay lingering strongly enough to keep me

looking for the series decades later. Despite my nostalgic enthusiasm for the show, in

all honesty, in the cold light of day, it’s not too hard to see why the BBC never

repeated or previously released SUPERNATURAL on other formats. It’s short on shocks,

and over-heavy on Freudian overtones, with little to titillate or terrify the typical

modern horror fan. It isn’t as satisfying or accessible as the BBC’s GHOST STORIES FOR CHRISTMAS – rightly still seen as setting the standard for vintage TV horror – but taken on its own merits, as a camp, creepy curio, SUPERNATURAL still has much to offer the authentic gourmet of Gothic entertainment.