It is St George’s Day, a day where we indulge in typical English pastimes. Such as bickering. Traditionally, someone begins by contrasting how St Patrick’s Day is celebrated, while that of our own patron saint is neglected. Usually someone will now observe that George wasn’t an Englishman at all, but a Turk/Georgian/Syrian/Geordie. This is customarily followed by rather vague and feeble accusations of racism. Right-wingers must now accuse those failing to celebrate of being traitorous, bed-wetting Trots, while their liberal counterparts must hiss darkly about the English flag becoming the sole preserve of goose-stepping, Imperialist hooligans. None of which I have a problem with – like all good Englishmen I love a pointless argument, and will punch the first person to suggest otherwise – but I fear it rather misses the point.

It is St George’s Day, a day where we indulge in typical English pastimes. Such as bickering. Traditionally, someone begins by contrasting how St Patrick’s Day is celebrated, while that of our own patron saint is neglected. Usually someone will now observe that George wasn’t an Englishman at all, but a Turk/Georgian/Syrian/Geordie. This is customarily followed by rather vague and feeble accusations of racism. Right-wingers must now accuse those failing to celebrate of being traitorous, bed-wetting Trots, while their liberal counterparts must hiss darkly about the English flag becoming the sole preserve of goose-stepping, Imperialist hooligans. None of which I have a problem with – like all good Englishmen I love a pointless argument, and will punch the first person to suggest otherwise – but I fear it rather misses the point.

Moving back to my childhood momentarily, when I was a kid, I liked to go to the London Dungeon every year. These days it’s a popular franchise, with branches across Europe. A haunted-house-style attraction, it’s full of animatronic gimmicks and out-of-work actors in white face-paint, jumping out at punters, or insulting or flirting with them in that curious accent you only ever hear in dodgy historical re-enactments. But in the early years, when I went, it was more like a grisly waxworks, focused on tableaux of authentic nasty episodes from our past. Frankly I preferred that, but I digress… The reason for this digression is that they had a couple of exhibits considered too gruelling for the casual visitor, shielded behind curtains with a warning emblazoned on them. Of course, this was quite irresistible. In one such taboo tableau was St George, being laboriously sawed in half.

Unsurprisingly, this made an impact on me, and ever since that’s the story of St George I remember, rather puzzled why others only talk of matters draconic. Many early Christians would have shared my sentiments. For whatever else you might feel about George, his dragon-slaying activities were incidental to the point of irrelevance in terms of his canonisation. For, what gets you sanctified in the Catholic church is dieing for the cause in the most dramatic, pointless, and preferably painful, fashion possible while continuing to irritate your persecutors with pious platitudes. In that department, George outstrips pretty much all of the competition. His death was a practical encyclopedia of the torturer’s art, that lasted not minutes, days, or even weeks, but seven fucking years! By comparison, JC’s time on the cross at Golgotha was a pleasant afternoon in the great outdoors.

So, in the spirit of celebrating our national day, I’ve hunted down the best account I could find of George’s interminable end. It has all the characteristics of authentic Early Christian lore: Pythonesque levels of silliness, childishly petty and spiteful sniping at rival religions, plus worryingly enthusiastic levels of sadomasochistic excess. I suspect we don’t hear so much of this aspect of the St George story because some scholars find it distastefully gruesome while others are aware that its gloriously, nasty tone of hysterical absurdity rather tend to expose the true colour of Christianity’s roots. But this is the real reason why St George is still remembered as a saint, not any hot action with scaly mythical characters. This version is borrowed from the Medieval Institute of Kalamazoo, Michigan

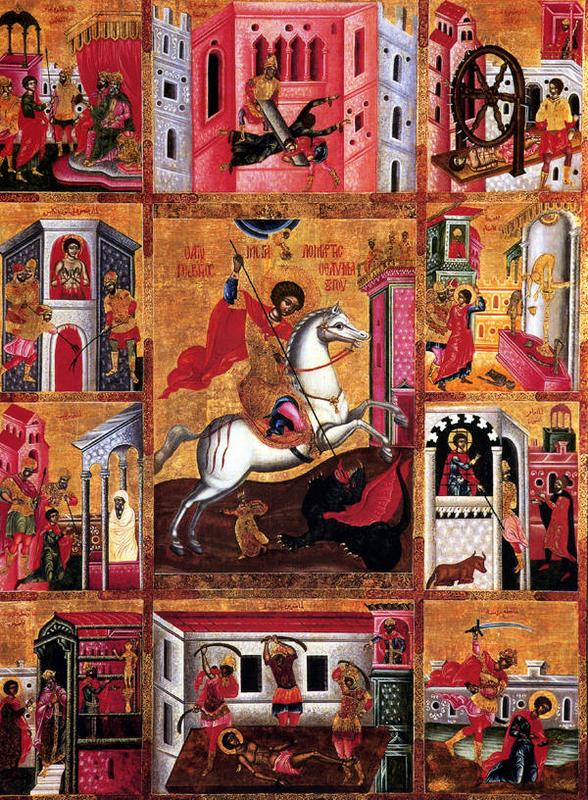

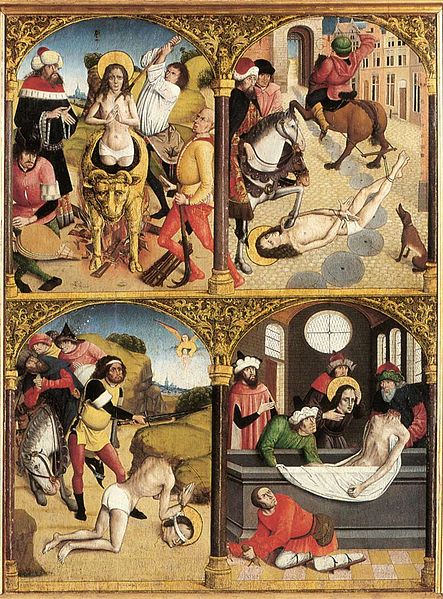

George, a military leader under Dacian, “king of the Persians,” inaugurates his seven years of torture by boldly coming forward to confess his belief in Christ, as Dacian is preparing to persecute Christians in the area. At Dacian’s order, George is stretched out on the rack and ripped to shreds with flesh hooks, harnessed to machines that draw him apart, and then beaten, after which salt is poured into his wounds, which are rubbed with a haircloth. He is then pressed into a box pierced with nails, impaled on sharp stakes, plunged into boiling water, and has his head crushed by a hammer. All to no avail. God comforts George in prison and informs him that he will die three deaths before entering Paradise. Dacian, confounded, summons the magician Athanasius who shows his mettle by splitting an ox in half and having each half return to life whole. Undaunted, George gulps down two portions of the magician’s poison, at which point the magician confesses Christ and is summarily executed by the Persian ruler and George is returned to prison. The next day he is lacerated on a wheel of swords, cut into ten pieces, and thrown into a well that is sealed with a stone. God appears with the archangel Michael to resurrect the saint, at which point the officer in charge, Anatholius, is converted with nearly 1,100 soldiers and one woman, all of whom are immediately executed. Dacian then redoubles his efforts: George is tied to an iron bed, molten lead is poured into his mouth and eyes after which sixty nails are driven into his skull, he is hung upside down over a fire with a stone tied around his neck, and he is shut into the revolving belly of a metal ox which is filled with swords and nails. Yet again at the end of the day the saint goes back to prison. To die his second death, George is sawed in two, boiled to bits, and just before he is buried, God, good to his word, resuscitates him after five days.

George, a military leader under Dacian, “king of the Persians,” inaugurates his seven years of torture by boldly coming forward to confess his belief in Christ, as Dacian is preparing to persecute Christians in the area. At Dacian’s order, George is stretched out on the rack and ripped to shreds with flesh hooks, harnessed to machines that draw him apart, and then beaten, after which salt is poured into his wounds, which are rubbed with a haircloth. He is then pressed into a box pierced with nails, impaled on sharp stakes, plunged into boiling water, and has his head crushed by a hammer. All to no avail. God comforts George in prison and informs him that he will die three deaths before entering Paradise. Dacian, confounded, summons the magician Athanasius who shows his mettle by splitting an ox in half and having each half return to life whole. Undaunted, George gulps down two portions of the magician’s poison, at which point the magician confesses Christ and is summarily executed by the Persian ruler and George is returned to prison. The next day he is lacerated on a wheel of swords, cut into ten pieces, and thrown into a well that is sealed with a stone. God appears with the archangel Michael to resurrect the saint, at which point the officer in charge, Anatholius, is converted with nearly 1,100 soldiers and one woman, all of whom are immediately executed. Dacian then redoubles his efforts: George is tied to an iron bed, molten lead is poured into his mouth and eyes after which sixty nails are driven into his skull, he is hung upside down over a fire with a stone tied around his neck, and he is shut into the revolving belly of a metal ox which is filled with swords and nails. Yet again at the end of the day the saint goes back to prison. To die his second death, George is sawed in two, boiled to bits, and just before he is buried, God, good to his word, resuscitates him after five days.

In addition to his own resilience, George’s miracles include changing thrones into trees, reviving oxen, healing a sick boy, and resurrecting and baptizing men, women, and children who have been dead for centuries.

Despite fastening a glowing iron helmet to the prisoner’s head, tearing and burning his body some more, and executing George a third time, Dacian fails to move the saint to sacrifice to Apollo and tries verbal persuasion instead. When George appears to consent, the delighted king invites him to the palace for the night during which the saint surreptitiously converts Dacian’s wife Alexandra, who is later executed as a result. George in the meantime goes to the temple of Apollo, whose statue promptly leaves the temple and confesses his fraudulence. The saint stamps his foot, and the ground swallows up the false god. Exasperated, Dacian pronounces George’s death sentence yet again. Before his execution, though, George prays and intercedes for those who remember his name and feast day. Having survived seven years of torture and three deaths, he is finally decapitated and gratefully ascends to Heaven.

So, what are we to make of this crazy episode of divine capers in the Middle East? For one thing, I don’t think the main impression I get here of George is one of bravery. More stupidity and stubbornness, blended with an irritating dose of low mendacity. Which are characteristics to be found among many Englishmen to be sure – one can see why the Houses of Parliament might approve, for example – but these aren’t traits inclined to make me swell with patriotic pride. The major plus point in this story is the ridiculous overdose of blood, gore and murder on display, leavened with elements of the supernatural. It is, in other words, an early horror story, and I most certainly approve of that. So perhaps we should revere St George as representative of England’s proud tradition as the home of horror, the patron saint of splatter. Certainly, if Hammer were thinking of getting into the ‘torture porn’ game, they could do a lot worse than making ‘St George: the Movie’ in fully, bloody 3D. It’d make ‘Hostel’ look like ‘Mary Poppins’.

So, what are we to make of this crazy episode of divine capers in the Middle East? For one thing, I don’t think the main impression I get here of George is one of bravery. More stupidity and stubbornness, blended with an irritating dose of low mendacity. Which are characteristics to be found among many Englishmen to be sure – one can see why the Houses of Parliament might approve, for example – but these aren’t traits inclined to make me swell with patriotic pride. The major plus point in this story is the ridiculous overdose of blood, gore and murder on display, leavened with elements of the supernatural. It is, in other words, an early horror story, and I most certainly approve of that. So perhaps we should revere St George as representative of England’s proud tradition as the home of horror, the patron saint of splatter. Certainly, if Hammer were thinking of getting into the ‘torture porn’ game, they could do a lot worse than making ‘St George: the Movie’ in fully, bloody 3D. It’d make ‘Hostel’ look like ‘Mary Poppins’.