Recent events have convinced many that, if we aren’t actually living in the End Times, we are certainly experiencing a period of unprecedented tumult and despair. The historian Paul Lay brought this to mind in a recent piece for History Today ‘Social media is abuzz with the question: is this the worst year in history?’ he begins. ‘The year so far has been a challenging one: a huge refugee crisis, born of the suffering in Syria and Iraq; increasing terrorism in Europe, a continent bewildered by Brexit; a failed coup and its sinister aftermath in the strategically critical state of Turkey; the Zika outbreak; growing racial tension in the United States; famine in northern Nigeria…’

As Lay, rightly points out, there have been far more traumatic times to be alive. Indeed, by most measures, most of us probably qualify as pampered. But this does touch on something I’ve long found fascinating. Namely, why do so many of take such perverse pleasure in pretending we are living in some kind of historical nadir? It’s a tendency I think I first really noticed when reading Barbara Tuchman’s acclaimed history book A Distant Mirror. It’s portrayal of the medieval world was well wrought, but her central thesis – that the apocalyptic era of the mid-1300s somehow reflected the tumult facing the world in the 1970s when it was written – was, frankly, far less convincing.

As Lay, rightly points out, there have been far more traumatic times to be alive. Indeed, by most measures, most of us probably qualify as pampered. But this does touch on something I’ve long found fascinating. Namely, why do so many of take such perverse pleasure in pretending we are living in some kind of historical nadir? It’s a tendency I think I first really noticed when reading Barbara Tuchman’s acclaimed history book A Distant Mirror. It’s portrayal of the medieval world was well wrought, but her central thesis – that the apocalyptic era of the mid-1300s somehow reflected the tumult facing the world in the 1970s when it was written – was, frankly, far less convincing.

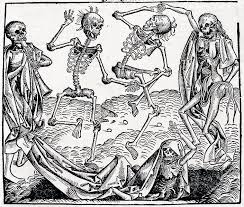

I would, in all honesty, support the case for the 14th century as a leading candidate for the worst in recorded history if pressed. Endemic total war, famine caused by a minor ice age, religious conflict, and violent widespread rebellion, all under the shadow of the Black Death, which claimed around half of the population in much of the Known World. It is true that from the ashes of such wholesale tragedy many positives emerged, but that is a story for another day (and the basis for a book I’ve been planning forever).

I would, in all honesty, support the case for the 14th century as a leading candidate for the worst in recorded history if pressed. Endemic total war, famine caused by a minor ice age, religious conflict, and violent widespread rebellion, all under the shadow of the Black Death, which claimed around half of the population in much of the Known World. It is true that from the ashes of such wholesale tragedy many positives emerged, but that is a story for another day (and the basis for a book I’ve been planning forever).

In my own lifetime, I think I’d single out the 1980s as a particularly grim period. The Cold War mushroom cloud spectre of nuclear annihilation hung over us in playgrounds across the globe. AIDS struck just as my generation came of age, forcefully connecting pleasure and death in our collective subconscious. Mad Cow Disease was still a frightening unknown, the prospect that what we’d eaten, courtesy of industrial farming techniques, might well fell a large number of us with a horrific neurological disorder. Worst case scenarios were competitive with the Black Death in terms of mortality, and even more fearsome in the way it claimed its victims by eating away at their grey matter.

In my own lifetime, I think I’d single out the 1980s as a particularly grim period. The Cold War mushroom cloud spectre of nuclear annihilation hung over us in playgrounds across the globe. AIDS struck just as my generation came of age, forcefully connecting pleasure and death in our collective subconscious. Mad Cow Disease was still a frightening unknown, the prospect that what we’d eaten, courtesy of industrial farming techniques, might well fell a large number of us with a horrific neurological disorder. Worst case scenarios were competitive with the Black Death in terms of mortality, and even more fearsome in the way it claimed its victims by eating away at their grey matter.

Some time back I was asked to pen a piece on the Apocalypse for the metal magazine Terrorizer. Researching it reminded me of the music I’d grown up with. While there were intimations of the apocalypse in 1970s rock – most notably ‘Electric Funeral’ by Black Sabbath perhaps – the transformation of the possibility of nuclear holocaust from a possibility to something that felt iminent, defined much of the music of my youth. Bands like Nuclear Assault dominated the cutting edge thrash movement in the 1980s, Nuclear Blast would go on to become one of the most successful genre labels in the world, while a search of the Metal Archives site throws up over 100 bands across the globe with ‘nuclear’ in their names.

Some time back I was asked to pen a piece on the Apocalypse for the metal magazine Terrorizer. Researching it reminded me of the music I’d grown up with. While there were intimations of the apocalypse in 1970s rock – most notably ‘Electric Funeral’ by Black Sabbath perhaps – the transformation of the possibility of nuclear holocaust from a possibility to something that felt iminent, defined much of the music of my youth. Bands like Nuclear Assault dominated the cutting edge thrash movement in the 1980s, Nuclear Blast would go on to become one of the most successful genre labels in the world, while a search of the Metal Archives site throws up over 100 bands across the globe with ‘nuclear’ in their names.

Yet it wasn’t all so dark. Most of us remained comfortable and fed – in the UK at least – and many of the threats we felt so keenly never manifested. But we do still take a perverse pleasure in pretending we live in ‘the worst of times’ don’t we? A quick skim across the internet reveals legions of jeremiads of every political persuasion insisting things are sliding into hell and that, by implication, were once much better in some mythical golden age.

But it’s balls isn’t it? Perhaps we feel the potential for loss greatest when we have most to lose? Maybe melodramatic doomsday declarations are a masochistic luxury afforded us by comparative comfort?

One thing I would suggest is that the worst of times are not when we fear that the world might end, but when we hope it will…