By day, Christopher JC is a literature academic, working in New York City. But by night, he toils as the Internet’s definitive Satanic Scholar, author of a new website dedicated to the Romantic interpretations of the Prince of Darkness, pioneered by the puritan poet John Milton in his epic masterpiece Paradise Lost some 350 years ago.

Christopher’s scholarship is impressive, but what really makes the site shine is his evident passion for the subject, transforming a topic that so often feels dry and dusty into something alight with vivacity and relevance. The trigger for the launch of Christopher’s Satanic Scholar site was the debut of the first episode of the high profile new Fox series Lucifer, in turn based upon the acclaimed comic of the same name by writer Mike Carey.

While at this early stage the jury’s still out on the TV show – though it’s provoked the regulation calls for a ban from right-wing Christian lobbies like the American Family Association – Christopher believes Carey’s Lucifer is one of the strongest interpretations of the Miltonic anti-hero to date. In the following interview I asked him about this, as well as the broader Romantic tradition, and how his academic studies dovetailed with his own views and philosophy…

GB: How important is Milton’s Paradise Lost in how we see the Devil today – did it change our view?

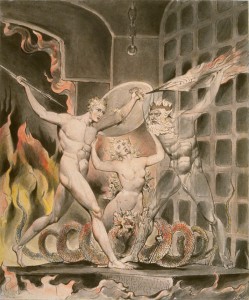

CJC: ‘Paradise Lost completely revolutionized the concept of the Devil, and I don’t believe we can overstress the significance of Milton’s Satan. Inadvertently, Milton’s magnificent portrait of the arch-rebel restored lustre to Lucifer’s much tarnished name and face, and the Miltonic Satan lent himself to the refined radicalism of the Romantics. Satan’s principled revolt was inspiring to a number of the era’s most prominent intellectuals, poets, and prose writers, such as Godwin, Wollstonecraft, Hazlitt, Blake, Shelley, and Byron. The Romantic Satanists’ penchant for putting the Miltonic Satan’s celestial revolt to earthly use as a sociopolitical countermyth has had a greater impact on the Devil’s majesty than the proceedings of any occult order, and there simply wouldn’t have been a Romantic Satanism without Milton’s Satan.’

GB: What drew you to the character of Lucifer in the first place?

CJC: ‘Even when I was a young kid, the story of Lucifer’s rebellion and fall was far more exciting than, say, Jesus doling out the loaves and the fishes. But the real dark epiphany for me was when I first encountered the eloquent fallen angel found in the pages of Paradise Lost later in life, awestruck as I was by the noble defiance of Milton’s Satan. I was always attracted to anti-heroes, and Milton’s Satan was the archetypal anti-hero—the challenger of omnipotent authority, dauntlessly defiant against all odds, heroically unbowed even in defeat. I was delighted to discover the tradition of Romantic Satanism and its Satanic School, presided over by Byron and Shelley. Their grand approach to life as little Lucifers—magnifying their own diabolical dispositions through adoption of the Miltonic Satan—was rather thrilling to me. Whether or not Milton was, as Blake famously theorized, “of the Devil’s party without knowing it,” I certainly was.’

GB: How do you rate the comic-book version of the character?

CJC: ‘I believe Mike Carey’s Lucifer—the Vertigo spinoff of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman—to be the place to find the Miltonic-Romantic Satan’s true heir. You undeniably get sympathetic Satans in George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman, Mark Twain’s Letters from the Earth, and Anatole France’s The Revolt of the Angels, but they are not on equal footing with Byron’s Promethean Lucifer, let alone Milton’s epic hero Satan. I daresay Carey’s Lucifer is. Visually, he is a blonde-haired, golden-eyed, smooth-faced, handsome Devil, whose wings are even restored to their former, feathery state. Portraying the rebellious Lucifer as beautifully angelic rather than frightfully or comically demonic is very much reminiscent of Romantic renditions of Milton’s Satan in the visual arts.’

Lucifer’s grand ambition of absolute autonomy is just as appealing as his outer beauty. Carey’s Lucifer may be so individualistic that he lacks a sense of loyalty to his brothers-in-arms (one of the finer qualities of Milton’s Satan), but his pride definitely has its virtues. Lucifer’s sole commandment is thou shalt have no gods, which includes him, and in this he is not only the Miltonic-Romantic Satan’s successor, but superior. Carey’s Lucifer is an icon of illustrious independence, and while I’m not sure how much of this will translate into the TV series adaptation, to even see his proud name gracing the small screen is rather surreal.’

GB: Do you believe in the Devil?

CJC: ‘No. I’m an atheist, so I definitely do not believe in the Devil as some cosmic bogeyman. I do however believe in the Devil insofar as I believe his myth and how it was told by Milton and exploited by the Romantics holds a great deal of power. Many secular humanists would like to see the Devil discarded into the dustbin of history, but I believe it would be a shame to simply shun the Miltonic-Romantic Satan because he’s fictional. I’m a fervent admirer of Lord Byron, but in this I am closer to Shelley, whose militant atheism embraced the symbolic potential of mythical figures like Satan or Prometheus. It was Baudelaire who said that “God is the only being who, in order to reign, doesn’t even need to exist,” and if that’s the case, I find the Miltonic Satan—“the most perfect type of male beauty,” according to monsieur Baudelaire—to be the most appropriate weapon against that reign, Satan’s nonexistence notwithstanding.’

GB: What would you say to people who think showing sympathy for the Devil is wrong or even dangerous?

CJC: ‘I would advise them to take a good hard look at the figure the Devil is defying. Even if we place theocrats aside for the moment and limit ourselves to mythology and literature, the biblical God strikes me as the epitome of genuine evil. In the Old Testament, God is worse than any maniacal tyrant plucked from the pages of history. To cite a few nasty examples, He promises to spread excrement upon the faces of His own people should they fail to glorify His name and to force them to eat the flesh of their own children should they disobey Him.’

Contrary to popular belief, the New Testament God is immeasurably worse, as the same Son of God who preaches turning the other cheek and love for enemies promises to see plunged into eternal flames all who fail to bend the knee to him and his Father. That divine despotism is what we see Milton’s Hell-doomed Satan defying in the opening books of Paradise Lost. Milton’s Satan lambasts “the tyranny of Heaven” and Byron’s Lucifer castigates God as an “Omnipotent tyrant,” and I think these diatribes possess such force.’

I find a great deal of sympathy for the Devil cropping up in atheist circles—however tongue-in-cheek it may be—and I believe that the more theocratic elements spread like cancers at home and abroad (is it coincidental that the holiest portion of the globe is also the most hellish?), the more appealing Lucifer will become. It’s the fallen Morningstar’s time to shine, and I’m proud to be a part of that…’

To sample some of Christopher’s Satanic Scholarship – which I would most heartily recommend – check out his website here. Meanwhile, once the Lucifer series has progressed, we plan on chatting again…